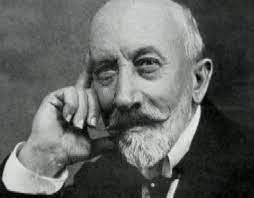

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès; 8 December 1861 - 21 January 1938) was a French illusionist, actor, and film director. He led many technical and narrative developments in the earliest days of cinema. Méliès was well known for the use of special effects, popularizing such techniques as substitution splices, multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, dissolves, and hand-painted colour. He was also one of the first filmmakers to use storyboards.

His films include A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904), both involving strange, surreal journeys somewhat in the style of Jules Verne, and are considered among the most important early science fiction films, though their approach is closer to fantasy. The 2011 film Hugo - produced by Martin Scorcese and Johnny Depp among others - was inspired by the life and work of Méliès.

Early life and education

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès was born 8 December 1861 in Paris, son of Jean-Louis Méliès and his Dutch wife, Johannah-Catherine Schuering. His father had moved to Paris in 1843 as a journeyman shoemaker and began working at a boot factory, where he met Méliès' mother. Johannah-Catherine's father had been the official bootmaker of the Dutch court before a fire ruined his business. Eventually the two married, founded a high-quality boot factory on the Boulevard Saint-Martin, and had sons Henri and Gaston; by the time their third son Georges, had been born, the family had become wealthy.

Georges Méliès attended the Lycée Michelet from age seven until it was bombed during the Franco-Prussian War; he was then sent to the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand. In his memoirs, Méliès emphasised his formal, classical education, in contrast to accusations early in his career that most filmmakers had been "illiterates incapable of producing anything artistic." However, he acknowledged that his creative instincts usually outweighed intellectual ones : "The artistic passion was too strong for him, and while he would ponder a French composition or Latin verse, his pen mechanically sketched portraits or caricatures of his professors or classmates, if not some fantasy palace or an original landscape that already had the look of a theatre set." Often disciplined by teachers for covering his notebooks and textbooks with drawings, young Georges began building cardboard puppet theatres at age ten and moved on to craft even more sophisticated marionettes as a teenager. Méliès graduated from the Lycée with a baccalauréat in 1880.

Stage career

After completing his education, Méliès joined his brothers in the family shoe business, where he learned how to sew. After three years of mandatory military service[citation needed], his father sent him to London to work as a clerk for a family friend and to improve his English. While in London, he began to visit the Egyptian Hall, run by the London illusionist John Nevil Maskelyne, and he developed a lifelong passion for stage magic. Méliès returned to Paris in 1885 with a new desire: to study painting at the École des Beaux-Arts. His father, however, refused to support him financially as an artist, so Georges settled with supervising the machinery at the family factory. That same year, he avoided his family's desire for him to marry his brother's sister-in-law and instead married Eugénie Génin, a family friend's daughter whose guardians had left her a sizable dowry. Together they had two children: Georgette,[5] born in 1888, and André, born in 1901.

While working at the family factory, Méliès continued to cultivate his interest in stage magic, attending performances at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, which had been founded by the magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin. He also began taking magic lessons from Emile Voisin, who gave him the opportunity to perform his first public shows, at the Cabinet Fantastique of the Grévin Wax Museum and, later, at the Galerie Vivienne.

In 1888, Méliès' father retired, and Georges Méliès sold his share of the family shoe business to his two brothers. With the money from the sale and from his wife's dowry, he purchased the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. Although the theatre was "superb" and equipped with lights, levers, trap doors, and several automata, many of the available illusions and tricks were out of date, and attendance to the theatre was low even after Méliès' initial renovations.

Over the next nine years, Méliès personally created over 30 new illusions that brought more comedy and melodramatic pageantry to performances, much like those Méliès had seen in London, and attendance greatly improved. One of his best-known illusions was the Recalcitrant Decapitated Man, in which a professor's head is cut off in the middle of a speech and continues talking until it is returned to his body. When he purchased the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, Méliès also inherited its chief mechanic Eugène Calmels and such performers as Jehanne D'Alcy, who would become his mistress and, later, his second wife. While running the theatre, Méliès also worked as a political cartoonist for the liberal newspaper La Griffe, which was edited by his cousin Adolphe Méliès.

Early film career

Méliès began shooting his first films in May 1896, and screening them at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin by that August. At the end of 1896 he and Reulos founded the Star Film Company, with Korsten acting as his primary camera operator. Many of his earliest films were copies and remakes of the Lumière brothers' films, made to compete with the 2000 daily customers of the Grand Café. This included his first film Playing Cards, which is similar to an early Lumière film. However, many of his other early films reflected Méliès' knack for theatricality and spectacle, such as A Terrible Night, in which a hotel guest is attacked by a giant bedbug. But more importantly, the Lumière brothers had dispatched camera operators across the world to document it as ethnographic documentarians, intending their invention to be highly important in scientific and historical study. Méliès' Star Film Company, on the other hand, was geared more towards the "fairground clientele" who wanted his specific brand of magic and illusion: art.

In September 1896, Méliès began to build a film studio on his property in Montreuil, just outside Paris. The main stage building was made entirely of glass walls and ceilings so as to allow in sunlight for film exposure and its dimensions were identical to the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. The property also included a shed for dressing rooms and a hangar for set construction. Because colours would often photograph in unexpected ways on black-and-white film, all sets, costumes and actors' makeup were coloured in different tones of gray. Méliès described the studio as "the union of the photography workshop (in its gigantic proportions) and the theatre stage." Actors performed in front of a painted set as inspired by the conventions of magic and musical theatre. For the remainder of his film career, he would divide his time between Montreuil and the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, where he "arrived at the studio at seven a.m. to put in a ten-hour day building sets and props. At five, he would change his clothes and set out for Paris in order to be at the theatre office by six to receive callers. After a quick dinner, he was back to the theatre for the eight o'clock show, during which he sketched his set designs, and then returned to Montreuil to sleep. On Fridays and Saturdays, he shot scenes prepared during the week, while Sundays and holidays were taken up with a theatre matinee, three film screenings, and an evening presentation that lasted until eleven-thirty."

In total, Méliès made 78 films in 1896 and 52 in 1897. By this time he had covered every genre of film that he would continue to film for the rest of his career. These included the Lumière-like documentaries, comedies, historical reconstructions, dramas, magic tricks, and féeries (fairy stories), which would become his most well-known genre. In 1897, Méliès was commissioned by the popular singer Paulus to make films of his performances. Because Paulus refused to perform outdoor, some thirty arc and mercury lamps had to be used in Méliès studio, one of the first times artificial light was used for cinematography. The films were projected as Paulus Chantant at the Ba-Ta-Clan. There, Paulus sat behind the cinema screen and sang the songs - thus giving the illusion of cinema with sound.

Méliès made only 27 films in 1898, but his work was becoming more ambitious and elaborate. His films included a historical reconstruction of the sinking of the USS Maine titled Divers at Work on the Wreck of the "Maine", the magic trick film The Famous Box Trick, and the féerie The Astronomer's Dream. In this film, Méliès plays an astronomer who has the Moon cause his laboratory to transform and demons and angels to visit him. He also made one of his first of many religious satires with The Temptation of Saint Anthony, in which a statue of Jesus Christ on the cross is transformed into a seductive woman.

Méliès made 48 films in 1899 as he continued to experiment with special effects, for example in the early horror film Robbing Cleopatra's Tomb. The film is not a historical reconstruction of the Egyptian Queen, and instead depicts her mummy being resurrected in modern times. Robbing Cleopatra's Tomb was believed to be a lost film until a copy was discovered in 2005 in Paris. That year, Méliès also made two of his most ambitious and well-known films. In the summer he made the historical reconstruction The Dreyfus Affair, a film based on the then-ongoing and controversial political scandal, in which the Jewish French Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused and framed for treason by his commanders. Méliès was pro-Dreyfus and the film depicts Dreyfus sympathetically as falsely accused and unjustly incarcerated on Devil's Island prison. At screenings of the film, fights broke out between people on different sides of the debate and the police eventually banned the final part of the film where Dreyfus returns to prison.

Later that year, Méliès made the féerie Cinderella, based on Charles Perrault's fairy tale. The film was six minutes long and had a cast of over 35 people, including Bleuette Bernon in the title role. It was also Méliès' first film with multiple scenes, known as tableaux. The film was very successful across Europe and in the United States, playing mostly in fairgrounds and music halls. American film distributors such as Siegmund Lubin were especially in need of new material both to attract their audience with new films and to counter Edison's growing monopoly. Méliès' films were particularly popular, and Cinderella was often screened as a featured attraction even years after its U.S. release in December 1899. Such U.S. filmmakers as Thomas Edison were resentful of the competition from foreign companies and after the success of Cinderella, attempted to block Méliès from screening most films in the U.S.; but they soon discovered the process of creating film dupes (duplicate negatives). Méliès and others then established in 1900 the trade union Chambre Syndicale des Editeurs Cinématographiques as a way to defend themselves in foreign markets. Méliès was made the first president of the union, serving until 1912, and the Théâtre Robert-Houdin was the group's headquarters.

No comments:

Post a Comment