Introduction

“The Oresteia” trilogy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus consists of the three linked plays “Agamemnon”, “The Libation Bearers” and “The Eumenides”. The trilogy as a whole, originally performed at the annual Dionysia festival in Athens in 458 BCE, where it won first prize, is considered to be Aeschylus’ last authenticated, and also his greatest, work. It follows the vicissitudes of the House of Atreus, from the murder of Agamemnon by his wife Clytemnestra, to the subsequent revenge wreaked by his son Orestes and its consequences.

Synopsis

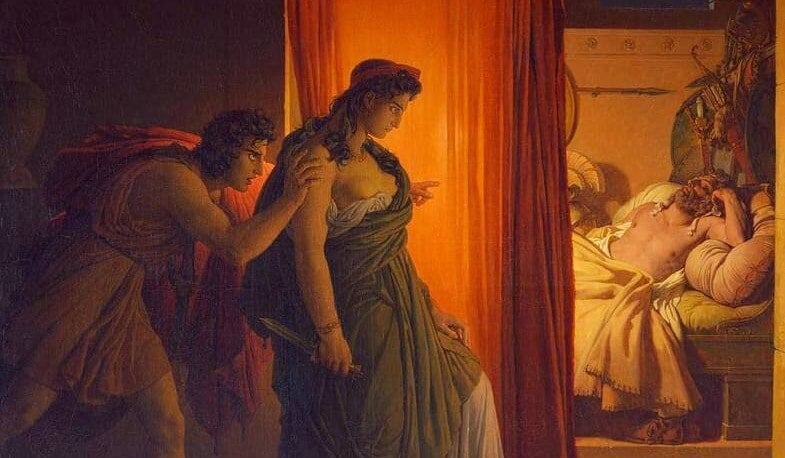

“Agamemnon” describes the homecoming of King Agamemnon of Argos from the Trojan War, along with his concubine Cassandra. His wife, Clytemnestra, however, had long been planning his murder (in concert with her lover, Aegisthus) as revenge for Agamemnon’s earlier sacrifice of their daughter, Iphigenia. For more detail, see the separate page on “Agamemnon”. “The Libation Bearers” deals with the reunion of Agamemnon's children, Electra and Orestes, and their revenge as they kill Clytemnestra and Aegisthus in a new chapter of the curse of the House of Atreus. For more detail, see the separate page on “The Libation Bearers”. “The Eumenides” tells of how Orestes is pursued to Athens by the vengeful Erinyes for the murder of his mother, Clytemnestra, and how he is tried before Athena and a jury of Athenians to decide whether his crime justifies the torment of the Erinyes. For more detail, see the separate page on “The Eumenides”.

Analysis

“The Oresteia” (comprising “Agamemnon”, “The Libation Bearers” and “The Eumenides”) is the only surviving example of a complete trilogy of ancient Greek plays (a fourth play, which would have been performed as a comic finale, a satyr play called “Proteus”, has not survived). It was originally performed at the annual Dionysia festival in Athens in 458 BCE, where it won first prize. Although technically a tragedy, “The Oresteia” as a whole actually ends on a relatively upbeat note, which may surprise modern readers, although in fact the term “tragedy” did not carry its modern meaning in ancient Athens, and many of the extant Greek tragedies do end happily. In general, the Choruses of “The Oresteia” are more integral to the action than the Choruses in the works of the other two great Greek tragedians, Sophocles and Euripides (particularly as the elder Aeschylus was only one step removed from the ancient tradition in which the whole play was conducted by the Chorus). In “The Eumenides” in particular, the Chorus is even more essential because it consists of the Erinyes themselves and, after a certain point, their story (and their successful integration into the pantheon of Athens) becomes a major part of the play. Throughout “The Oresteia”, Aeschylus uses a lot of naturalistic metaphors and symbols, such as solar and lunar cycles, night and day, storms, winds, fire, etc, to represent the vacillating nature of human reality (good and evil, birth and death, sorrow and happiness, etc). There is also a significant amount of animal symbolism in the plays, and humans who forget how to govern themselves justly tend to be personified as beasts.

Other important themes covered by the trilogy include: the cyclical nature of blood crimes (the ancient law of the Erinyes mandates that blood must be paid for with blood in an unending cycle of doom, and the bloody past history of the House of Atreus continues to affect events generation after generation in a self-perpetuating cycle of violence begetting violence); the lack of clarity between right and wrong (Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Orestes are all faced with impossible moral choices, with no clearcut right and wrong); the conflict between the old and the new gods (the Erinyes represent the ancient, primitive laws which demand blood vengeance, while Apollo, and particularly Athena, represent the new order of reason and civilization); and the difficult nature of inheritence (and the responsibilities it carries with it). There is also an underlying metaphorical aspect to the entire drama: the change from archaic self-help justice by personal revenge or vendetta to the administration of justice by trial (sanctioned by the gods themselves) throughout the series of plays, symbolizes the passage from a primitive Greek society governed by instincts, to a modern democractic society governed by reason. The tyranny under which Argos finds itself during the rule of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus corresponds in a very broad way to some events in the biographical career of Aeschylus himself. He is known to have made at least two visits to the court of the Sicilian tyrant Hieron (as did several other prominent poets of his day), and he lived through the democratization of Athens. The tension between tyranny and democracy, a common theme in Greek drama, is palpable throughout the three plays. By the end of the trilogy, Orestes is seen to be the key, not only to ending the curse of the House of Atreus, but also in laying the foundation for a new step in the progress of humanity. Thus, although Aeschylus uses an ancient and well-known myth as the basis for his “The Oresteia”, he approaches it in a distinctly different way than other writers who came before him, with his own agenda to convey.

Giới thiệu

Bộ ba tác phẩm The Oresteia của nhà soạn kịch Hy Lạp cổ đại Aeschylus bao gồm ba vở kịch liên quan "Agamemnon", "The Libation Bearers" và "The Eumenides". Trilogy như một tổng thể, ban đầu được trình diễn tại lễ hội Dionysia hàng năm ở Athena vào năm 458 trước Công nguyên, nơi nó được giải nhất, được xem là lần chứng thực cuối cùng của Aeschylus, và cũng là tác phẩm vĩ đại nhất của ông. Nó theo sau những thăng trầm của Nhà Atreus, do vụ ám sát của Agamemnon do vợ Clytemnestra, về cuộc trả thù sau đó do Orestes và những hậu quả của nó gây ra.

Tóm tắc

"Agamemnon" mô tả cuộc trở lại của vua Agamemnon của Argos từ Chiến tranh Troy, cùng với Cassandra của người hầu. Vợ ông, Clytemnestra, từ lâu đã lên kế hoạch giết người (trong buổi hòa nhạc với người yêu của cô, Aegisthus) để trả thù cho sự hy sinh sớm hơn của Agamemnon về con gái họ là Iphigenia. Để biết thêm chi tiết, xem trang riêng trên "Agamemnon". "The Libation Bearers" đề cập đến cuộc hội ngộ của trẻ em Agamemnon, Electra và Orestes, và trả thù của họ khi họ giết Clytemnestra và Aegisthus trong một chương mới của lời nguyền của Nhà Atreus. Để biết thêm chi tiết, xem trang riêng về "The Libation Bearers". "The Eumenides" nói về việc Orestes được theo đuổi bởi Athens Erinyes vì mưu sát mẹ, Clytemnestra, và cách ông ta bị xét xử trước Athena và một bồi thẩm đoàn của người Athena để quyết định liệu tội ác của ông có phải là lý do cho sự hành hạ Erinyes không. Để biết thêm chi tiết, xem trang riêng về "The Eumenides".

Phân tích

"Oresteia" (bao gồm "Agamemnon", "The Libation Bearers" và "The Eumenides") là ví dụ sống sót duy nhất của bộ ba hoàn chỉnh về vở kịch Hy Lạp cổ đại (một vở thứ tư, được thực hiện như là một tập cuối của truyện tranh, Kịch satyr gọi là "Proteus", đã không tồn tại). Ban đầu nó được trình diễn tại lễ hội Dionysia hàng năm ở Athens vào năm 458 trước Công nguyên, nơi nó được giải nhất. Mặc dù về mặt kỹ thuật một bi kịch, "The Oresteia" như một tổng thể thực sự kết thúc bằng một ghi chú tương đối lạc quan, có thể gây ngạc nhiên cho độc giả hiện đại, mặc dù thực tế thuật ngữ "bi kịch" không mang ý nghĩa hiện đại của nó ở Athens cổ đại, và nhiều tiếng Hy Lạp còn tồn tại Bi kịch kết thúc hạnh phúc. Nói chung, Choruses của "The Oresteia" là phần không thể tách rời của hành động hơn Choruses trong các tác phẩm của hai nhà du hành Hy Lạp vĩ đại khác, Sophocles và Euripides (đặc biệt là Aeschylus cao tuổi chỉ là một bước đi được gỡ bỏ từ truyền thống cổ xưa, trong đó Toàn bộ vở được tiến hành bởi Chorus). Trong "The Eumenides", Chorus thậm chí còn cần thiết hơn nữa vì nó bao gồm bản thân Erinyes, và sau một thời điểm nào đó, câu chuyện của họ (và sự hội nhập thành công của họ vào thần Athena) trở thành một phần quan trọng của vở kịch. Trong suốt "The Oresteia", Aeschylus sử dụng rất nhiều ẩn dụ tự nhiên và các biểu tượng, chẳng hạn như chu kỳ mặt trời và mặt trăng, ban đêm và ban ngày, bão, gió, lửa ... để đại diện cho tính chất hoài bão của thực tế con người (tốt và xấu, Cái chết, nỗi buồn và hạnh phúc, vv). Ngoài ra còn có một số lượng biểu tượng biểu tượng thú vật trong các vở kịch, và những con người quên làm thế nào để cai trị một cách chính đáng có xu hướng được nhân cách hóa thành những con thú.

Các chủ đề quan trọng khác bao gồm: tính chất chu kỳ của các tội phạm về máu (luật pháp của Erinyes quy định máu phải được trả bằng máu trong một chu kỳ bất diệt, và lịch sử đẫm máu của Nhà Atreus tiếp tục Ảnh hưởng đến sự kiện sau thế hệ sau khi xảy ra chu kỳ bạo lực tự hoãn); Sự thiếu rõ ràng giữa đúng và sai (Agamemnon, Clytemnestra và Orestes đều đang phải đối mặt với những lựa chọn đạo đức không thể, không có sự rõ ràng đúng hay sai); Cuộc xung đột giữa các vị thần cũ và mới (Erinyes đại diện cho luật cổ đại, nguyên thủy đòi trả thù máu, trong khi Apollo, và đặc biệt là Athena, đại diện cho trật tự mới của lý trí và nền văn minh); Và bản chất khó khăn của thừa kế (và trách nhiệm nó mang theo). Cũng có một khía cạnh ẩn dụ cơ bản đối với toàn bộ bộ phim truyền hình: sự thay đổi từ công việc tự cứu bản thân bằng cách trả thù cá nhân hoặc thù hận cho công lý bằng cách xét xử (do chính các vị thần) thực hiện trong suốt chuỗi các vở kịch, tượng trưng cho sự xuất hiện của một bộ phim Xã hội Hy Lạp nguyên thủy bị chi phối bởi bản năng, đối với một xã hội dân chủ hiện đại bị chi phối bởi lý trí. Sự chuyên chế theo đó Argos thấy mình trong suốt quy luật của Clytemnestra và Aegisthus tương ứng một cách rộng rãi với một số sự kiện trong sự nghiệp tiểu sử của Aeschylus. Ông được biết là đã có ít nhất hai lần viếng thăm triều đình của hoàng đế Sicier Hieron (cũng như một số nhà thơ nổi tiếng khác trong thời của ông), và ông đã trải qua quá trình dân chủ hóa Athens. Sự căng thẳng giữa chế độ chuyên chế và dân chủ, một chủ đề phổ biến trong bộ phim Hy Lạp, rõ ràng có thể thấy được trong suốt ba vở kịch. Đến cuối của bộ ba, Orestes được xem là chìa khóa, không chỉ để chấm dứt lời nguyền của Nhà của Atreus, mà còn là nền tảng cho một bước tiến mới trong sự tiến bộ của nhân loại. Vì vậy, mặc dù Aeschylus sử dụng một huyền thoại cổ xưa và nổi tiếng làm cơ sở cho "The Oresteia", ông đã tiếp cận nó theo một cách khác biệt rõ nét so với các nhà văn khác đã đến trước mặt ông, với chương trình truyền thông của riêng ông.

No comments:

Post a Comment