The articles below are recorded from existing media channels, from highly reliable channels, not extremist, authoritarian... the content is original and has not been edited in any other way. These are the views of the author of the article and not of the reposter... To avoid intentional or unintentional misunderstandings, all articles clearly cite the source at the end of each article... Refer to it to have objective thoughts according to your own opinion, and especially please do not take any actions that cause inconvenience to others...

- In May,2024

Vietnam spoke out about Cambodia's construction of the Funan Techo canal

May 5, 2024 - On the evening of May 5, responding to a reporter's question asking for Vietnam's reaction to Cambodia's recent statements on the implementation of the Funan Techo canal project, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Pham Thu Hang emphasized: "Vietnam always values and gives top priority to good neighborly relations, traditional friendship, comprehensive and long-term sustainable cooperation with Cambodia in its foreign policy."

According to the spokesperson, Vietnam wants the two countries' relationship to develop more deeply, practically and effectively in all fields for the benefit of the two peoples.

The spokesperson said that the leaders of the two Parties and States have affirmed that the historical tradition of solidarity and close relations between Vietnam and Cambodia is a very important factor and a source of great strength for the cause. fighting for national liberation, protecting past independence as well as the construction and development of each country today. Vietnam always supports, rejoices and highly appreciates the achievements Cambodia has achieved in recent times.

Regarding the Funan Techo canal project, the spokesperson said, Vietnam is very interested in and respects Cambodia's legitimate interests in the spirit of the 1995 Mekong Agreement, in accordance with relevant regulations of the River Commission. Mekong and the traditional friendly neighborly relationship between the two countries.

The spokesperson expressed: "We hope that Cambodia will continue to coordinate closely with Vietnam and other countries in the Mekong River Commission to share information and fully assess the impact of this project on water resources and resources." water resources and ecological environment of the Mekong sub-region along with appropriate management measures to ensure harmony of interests of riparian countries, effective and sustainable management and use of water resources and resources. Mekong River's water resources, for the sustainable development of the basin, the close solidarity between riverine countries and the future of future generations.

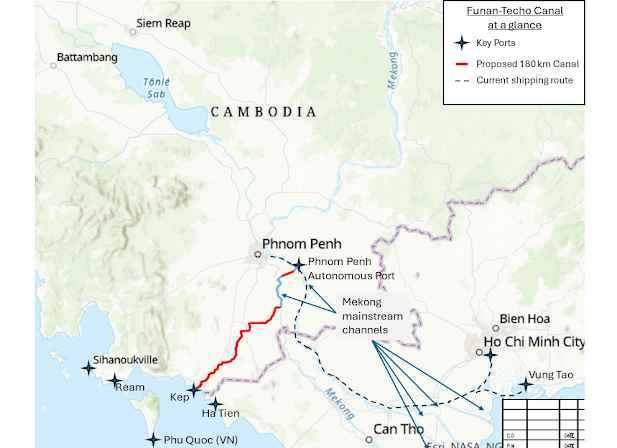

According to Khmer Times, the Funan Techo canal is expected to be 180km long, connecting from Prek Takeo on the Mekong River to Prek Ta Ek and Prek Ta Hing on the Bassac River, then emptying into the Gulf of Thailand in southwestern Cambodia.

The canal passes through four provinces including Kandal, Takeo, Kampot and Kep, with about 4 million people living on both sides.

Funan Techo is expected to have a width of 100m upstream, 80m downstream, 5,4m deep, including a navigation depth of 4,7m and a safety margin of 0,7m, allowing full load cargo ships. Up to 3.000 tons pass through in the dry season, 5.000 tons in the rainy season. The canal has two lanes, vehicles can enter and exit and avoid each other safely.

The project has an estimated cost of 1,7 billion USD, including 3 waterway dams, 11 bridges and 208km of roads on both sides, expected to be implemented by Chinese company CRBC in the form of build - operate - transfer. This form allows the construction party to operate and earn profits for about 50 years. The canal construction period is expected to last about 4 years.

Impacts of Cambodia’s Funan Techo Canal and Implications for Mekong Cooperation

May 9, 2024 - How a new Belt and Road project in Cambodia could increase water and flood risks in Vietnam and weaken the 1995 Mekong Agreement.

Cambodia has every right to construct the Funan Techo Canal, a project that gives Cambodia water access the Gulf of Thailand for commercial and other uses. But the way Cambodia’s government has communicated its intents to build the canal is creating diplomatic friction with its neighbor Vietnam. Regional tensions and environmental impacts of the project will be reduced if Cambodia follows the letter of the 1995 Mekong Agreement. This article analyzes official documents and recent public discourse around the canal to examine environmental impacts and gaps where more information is needed. The article suggests actions concerned parties can take to prevent a deterioration of Mekong cooperation.

Summary

The proposed 180km Funan Techo Canal project in Cambodia will deliver significant transboundary impacts to water availability and agricultural production in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, with acute impacts to An Giang and Kien Giang provinces. The project will convert many existing narrow, low-levee canals in Cambodia which currently do not alter wet season flooding pathways into wider, high-levee canals which will reduce wet season flooding in both Cambodia and Vietnam. Wet season flooding provides positive benefits to both Cambodia and Vietnam by driving agricultural production and creating large, natural wetlands that provide economic security to millions of people and robust biodiverse habitats. Floodplain alterations will cause wet season flooding to attack the canal’s high levees and result in higher than anticipated construction and maintenance costs across the life cycle of the canal.

Currently the only document outlining the project’s functions, impacts, and blueprints is the August 8, 2023 CNMC notification document to the MRC. In the notification document, the project is incorrectly designated as a “tributary” project even though the project connects to two Mekong mainstream channels. The incorrect tributary designation allows the Cambodian government to avoid 1995 Mekong Agreement prior consultation protocols and hastily commence construction without subjecting the project to a technical review and other processes which could improve the design and operation of the canal.

Further, after the August 2023 CNMC notification, the official narrative on the canal’s functions has changed to include irrigation benefits which are not discussed in the CNMC notification document and could have additional impacts to the water availability in the delta. The changing narrative on the canal’s functions is another valid cause for concern.

Recommendation

Given the severe potential transboundary impacts, evidence of changing functional descriptions over time, incorrect designation of the project, and an overall lack of project documentation, concerned parties should advocate for the CNMC to correctly designate the canal as a mainstream project. This will initiate MRC prior consultation processes which provide a pathway and sufficient time to comprehensively assess canals impacts, propose mitigation changes, and explore alternatives. Failing to initiate the MRC consultation processes will result in an erosion of the MRC’s ability to carry out its mandate set forward in the 1995 Mekong Agreement and set precedent for other MRC member countries to ignore their international treaty responsibilities when developing future projects.

Project Overview

The 180km Funan Techo Canal project was approved by Cambodia’s Council of Ministers in 2023 and a notification document was sent from the Cambodia National Mekong Committee (CNMC) to the Mekong River Commission (MRC) on August 8, 2023, two weeks prior to PM Hun Sen’s resignation. The $1.7 billion Belt and Road project will be built as a build-operate-transfer (BOT) project, likely by Chinese state-owned enterprise China Bridge and Road Corporation (CRBC) with construction slated to begin in 2024 and end in 2027. Recent media reports suggest the Chinese BOT owner will have a lease on the project for 40-50 years.

The canal would permit barges to move goods from Phnom Penh to a new port facility at Kep to be loaded onto ocean-bound ships. Currently, ocean-bound shipping from Phnom Penh must pass through Vietnam’s Mekong Delta to ports near Ho Chi Minh City. The CNMC notification document states the project will promote “the development of Cambodia’s integrated transport system, ensuring the safety of the national water transport network, reducing social logistics costs, driving Cambodia’s economic and social development to achieve new breakthroughs and promoting the coordinated development of regional economy.”

|

Figure A: This is a modified version of a map provided in the MRC notification document.

Incorrect Notification to the MRC

The MRC is not yet involved at an appropriate level because the CNMC has designated the project incorrectly in the notification document as a “tributary” project even though the canal clearly connects to two branches or channels of the Mekong mainstream (See figure A): the channel commonly referred to as the Mekong mainstream and the Bassac Channel. These are channels of the mainstream because they both carry the mainstream’s water. By definition, a tributary cannot carry mainstream water. Yet, even former Prime Minister Hun Sen has publicly stated that the canal does not connect to the Mekong Mainstream. Regardless of how the Bassac Channel is defined, canal blueprints submitted by the CNMC prove this claim to be inaccurate.

Concerned parties should advocate for the CNMC to change the project designation from “tributary” to “mainstream” as a means to initiate mandated prior consultation processes for mainstream projects.

Article 5 of the Mekong Agreement requires prior consultation for any project that connects to the Mekong mainstream and alters mainstream flow. It is still possible for the CNMC to properly designate the canal as a mainstream project as required by the 1995 Mekong Agreement. This would initiate the MRC Procedures for Notification, Prior Consultation, and Agreement (PNPCA), initiating the prior consultation process which includes regional stakeholder forums in all MRC countries and requires submission of all related project documents to the MRC Secretariat and the National Mekong Committees of Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos. The prior consultation process would also include an expert-led technical review process that will improve the environmental mitigation outcomes of the project design.

There is precedent for pursuing a change to the notification document. In 2013, the Lao PDR National Mekong Committee incorrectly designated the Don Sahong Hydropower Project as a “tributary” dam even though it was clearly sited on a channel of the Mekong mainstream. Diplomatic pressure from the CNMC and development partners such as the United States, Australia, and Japan effectively convinced the Lao PDR National Mekong Committee to change the project designation from “tributary” to “mainstream”. The change initiated the prior consultation process which provided time to give full assessment of the project’s impacts and added critically important fisheries mitigation infrastructure that currently facilitates fish migration around the dam site.

Potential Inter-basin Diversion

The notification document states that the project will have “no significant impact on (and thus no negative implication to) the Mekong River system’s daily flow and annual flow volumes.” The document refers to a navigation lock system (See Figure B) that will prevent water from leaving the Mekong mainstream and flowing into the Bassac channel. The lock system is also designed to prevent water from flowing from the Mekong Basin into the Gulf of Thailand. If properly managed and operated, the lock system can indeed prevent significant outflow from the Mekong mainstream channels, and as such river levels downstream in Vietnam could be minimally affected.

|

| Figure B: Canal blueprint submitted as part of the MRC notification document. |

However, by including the mitigation efforts of navigation locks into the canal’s current design does not create a pathway for the CNMC to circumvent rules set forth in the 1995 Mekong Agreement. The canal has the potential to divert water from the Mekong Basin to coastal estuaries in Cambodia outside of the Mekong Basin (and into the Gulf of Thailand). This qualifies as an inter-basin diversion. Article 5 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement states all inter-basin diversion projects are subject to MRC prior consultation.

Concerned parties should request more information on the design, maintenance, and operations of the navigation lock system. Further, the government of Cambodia should provide real-time reporting on lock operations throughout the life cycle of the canal project in order to ensure there is no significant transfer of water from the Mekong mainstream to the Bassac Channel or from the Mekong Basin to the Gulf of Thailand.

Potential Dry Season Intra-basin Use for Irrigation

In a social media post on April 9, 2024, former Prime Minister Hun Sen wrote in reference to the Funan Techo Canal that “This vital infrastructure facilitates agricultural activities by providing water for crop cultivation…” and the irrigation function of the canal has been mentioned in other media articles written by Cambodian authors. The canal’s irrigation benefits were also discussed in an English language video interview by Deputy Prime Minister Sun Chanthol on May 1, 2024. However, the CNMC notification document does not mention irrigation nor agricultural benefits in the section entitled “Positive Impacts” where the canal’s other functions are outlined. If secondary and tertiary canals for the facilitation of irrigation and agricultural purposes are to be built as part of the canal’s design, these designs are not provided in the project blueprints submitted as attachments to the CNCM notification document. If the canal does have an irrigation use, then it will at times use much more than the 3 m3/s of Mekong mainstream and Bassac Channel (also mainstream) flow outlined in the CNMC notification document. As such, Vietnam’s downstream concerns of loss of Mekong flow to Vietnam’s Mekong Delta are entirely justified.

|

| Figure C: Pathway of the Funan Techo Canal juxtaposed on top of an animation of the a normal Mekong Floodpulse (derived from 2018 Sentinel-1 SAR imagery). |

The canal passes through an active floodplain (see Figure C) which is flooded for several months during the wet season, so it is logical to assume that water used for irrigation purposes will primarily be extracted from the Mekong during the dry season. Article 5 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement states dry season utilization of mainstream flow for intra-basin use (use within the Mekong Basin) is subject to MRC prior consultation and also an agreement between MRC member countries, a diplomatic exercise never before undertaken by the MRC.

If the canal is intended for dry season irrigation use, the CNMC should update its notification document to clearly state this function and request prior consultation in accordance to Article 5 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement. Until this happens, concerned parties should seek clarity on the irrigation function of the canal and request an updated notification document.

Transboundary Floodplain Impacts

Geospatial analysis suggests the canal will widen many existing low levee canals and cut across floodplains and rural lands which currently do not have canals or waterways (Figure D). The existing low levees permit the natural flow of high floods during the wet season. It can be inferred from the notification document that in order to prevent the two-lane canal and related navigation locks and water gates from flood damage, high levees will need to be constructed.

Further, more than 1300 square kilometers of transboundary floodplain could become significantly drier as a result of the canal’s inability to pass seasonal floods through its high-levee system (yellow-black circles in Figure E). This impacted area spans significant parts of southern Cambodia and Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. In Cambodia, the impacted area includes the Boueng Prek Lapouv wetland which, according to an IUCN report, “represents one of the largest remnants of seasonally-inundated grasslands in the Lower Mekong Region, at over 8,300 hectares in size. It is one of 40 globally Important Bird Areas (IBAs) identified as key sites for conservation in Cambodia and one of three sarus crane (Grus antigone) Conservation Areas.” The Cambodian government has officially designated Boeung Prek Lapouv as a Protected Landscape Area and has submitted it for international Ramsar designation. International conservation organizations such as IUCN, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust are engaged in collaborative activities with Cambodian government agencies supported by development aid.

In Vietnam, a portion of the Kenh Vinh Te Canal in An Giang was lowered in the last decade to permit seasonal flooding to flow into and irrigate much of the western portion of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Seasonal flooding also passes naturally over the Kenh Vinh Te Canal in Kien Giang Province to provide natural irrigation there. This area is labelled as “Flood corridor” in Figure E. Without alterations to the canal’s design or proper mitigation, this large area of the Mekong Delta along with a signification portion of Cambodia’s floodplain along its border will be severely impacted. The reduction in natural flooding and increased dryness will lead to loss of industrial scale agricultural production. The reduction of seasonal flooding and its impact on industrial scale agriculture can be determined by studies. The Stimson Center Southeast Asia Program assesses that the most significant environmental impacts of the canal will be delivered via alteration of the transboundary floodplain between Cambodia and Vietnam. The CNMC notification document mentions nothing of these floodplain impacts.

Concerned parties should seek clarity on transboundary floodplain impacts and request an update to the CNCM notification document. If the specific height, location, and design of the canal’s levees are known, then it will be possible to model and determine the impacts introduced to the transboundary floodplain.

Existing Alternatives

All infrastructure projects should consider the costs and benefits of alternative projects prior to construction. Alternative canal pathways could entirely avoid alterations to the transboundary floodplain and therefore avoid reductions to industrial scale agriculture in Vietnam and negative impacts to the Boeung Prek Lapouv wetland.Since the canal’s limited depth cannot facilitate the passage of large container shipping, perhaps it is more economically prudent for goods which utilize the canal via 1,000-ton ships to utilize other means of linear transportation such as highways or railway. In 2023, a $2 billion Belt and Road expressway from Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville’s deep water port was completed. While highway transport is more expensive than river transportation, full utilization of the highway as an alternative to the canal would avoid all transboundary impacts to Vietnam and could avoid the need for a costly deep-water port at Kep (which would come with its own environmental and social impacts). An existing railway line from Phnom Penh to the Sihanoukville deep water port can also be improved, likely at much lower cost than the life cycle cost of the canal, particularly when considering unanticipated expenses of maintaining and rebuilding the canal’s levees after flood damage. Concerned parties should suggest these alternatives to avoid the transboundary impacts and the high unanticipated costs of the canal.

Conclusion

While the Cambodian government has every right to develop infrastructure within its sovereign territory, as a signatory to the 1995 Mekong Agreement its government needs to act in accordance to international law when it comes to projects within the Mekong Basin. Incorrect interpretation of the Mekong Agreement opens the door for other signatory countries to skirt the rules on future upstream projects which could deliver profound transboundary impacts to Cambodia, such as Thailand’s Khong-Chi-Mun massive water diversion project. Over the past decade Cambodia has been among the most vigilant countries in terms of holding other MRC member countries accountable to the 1995 Mekong Agreement. By initiating the prior consultation process, Cambodia will maintain its legacy as a champion of the Mekong Agreement and the MRC’s regional consultations and expert technical review will allow specific concerns to be addressed and common ground identified.

By Brian Eyler; Regan Kwan; Courtney Weatherby Southeast Asia, May 9, 2024

China’s Strategic Canal in Cambodia May Cause Regional Destabilization

May 11, 2024 - Chinese-backed canal project aims to connect the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh on the Mekong river with the sea by 2028, removing the need to go via Vietnam.

The Funan-Techo canal will be financed, built, operated and owned by a Chinese state-owned firm at a cost of $1.7 billion. The Cambodian government has been conducting an intense propaganda campaign about the supposed merits of the project. But the official rationale is confused, incomplete and contradictory.

Cambodia has an existing deep-water port at Sihanoukville, which is not mentioned a single time in the studies purporting to show the economic advantages of the Funan-Techo canal. The Sihanoukville port, built with French help in 1961, is a vital conduit for Cambodia’s international trade. The port today is badly managed, with its administration undermined by corruption, to the detriment of its competitiveness against ports in neighbouring countries.

The railway line which was also built with French help in the 1960s was designed to reinforce the port’s role. But the line has now been virtually abandoned in terms of international trade. This is a result of long-term negligence and incompetence on the part of Cambodia’s former prime minister Hun Sen, who, after ruling the country as a dictator since the 1980s, handed over official power to his son Hun Manet in 2023.

Calculations as to the future profitability of the Funan-Techo canal are not credible. They are undermined by the fact that they deliberately ignore the possibilities provided by the port of Sihanoukville, if it was better managed in conjunction with a functioning railway line. Taking account of these possibilities would allow a more realistic assessment. It’s inconceivable that the canal can play a role in Cambodia’s international maritime trade without relying on the country’s only deep-water port at Sihanoukville.

Geopolitical changes

Lack of transparency and public accountability are consistent features of the Cambodian regime’s policies across the board. It’s clear, however, that the real reasons for the canal project are not economic. Hun Sen’s vanity is insatiable. “Techo” is a distinctive honorific title which he uses and which he has decided to attach to the project, perhaps in a late bid to prevent history from judging him as a Khmer Rouge defector turned puppet Cambodian leader installed by Vietnam forty years ago.

This, he hopes, will be achieved by ensuring that Phnom Penh’s small river port no longer has to rely on Vietnam, which controls the downstream ports on the River Mekong near the South China Sea.

This question of commercial independence from Vietnam didn’t have much importance until recently because the Phnom Penh river port, since the construction of the maritime port at Sihanoukville, served mainly to support trade between Cambodia and Vietnam. The idea of reducing dependence on Vietnam is a new preoccupation for Hun Sen. This new priority reflects geopolitical changes which have recently seen Cambodia pass into the Chinese orbit.

These considerations mean that the canal, from Hun Sen’s perspective, has to be built at all costs. The canal is strategically important for China, and Beijing will deal with all aspects of the project, including feasibility studies, financing and day to day management for 50 years.

A strategic canal for China

The map above shows the strategic character of the canal for Beijing. The project will give China access to the Gulf of Thailand from southern China passing via Laos and Cambodia, but avoiding Vietnam. Almost all of the Mekong, from Tibet to the Gulf of Thailand, will be a strategic river under Chinese control.

The waterway will allow the transportation of goods, including weapons and ammunition, from China to the Gulf of Thailand. The canal will reach the sea close to the Chinese military base at Ream, which is also on Cambodian territory.

Use of the canal for international trade, however, will be complicated by the fact that Hun Sen initially came to power in Cambodia as a puppet of Vietnam. The Phu Quoc island and the surrounding waters facing the planned canal belong to Vietnam, following a sea border treaty with Vietnam signed by Hun Sen in 1982. This means that Vietnam will be in a position to block any passage from Cambodia’s territorial waters facing the canal to international waters. The transportation of arms and ammunition by China to its base at Ream won’t be affected by this problem as the base and the canal are both inside Cambodia.

Vietnam has already raised concerns that the project will lead to waterflow being diverted away from its stretch of the Mekong. Research from a state-backed Vietnamese institute, the Oriental Research Development Institute (ORDI), has rejected the Cambodian claim that the canal has purely socio-economic purposes and argues that regional security will be affected.

To reach the Gulf of Thailand Chinese military vessels currently have to sail at sea and are perhaps too visible for Beijing’s liking. The ORDI says that the locks on the canal can be used to create sufficient water depths for military vessels to enter the canal either from the Gulf of Thailand, or from the Ream naval base. The one certainty is that the canal, in combination with the Ream facility, will lead to greater political tensions and heightened instability for the whole region.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author : Sam Rainsy, Cambodia’s finance minister from 1993 to 1994, is the co-founder and acting leader of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). May 11, 2024

The Funan Techo Canal Won’t Have A Military Purpose

May 23, 2024 : Arguments that Cambodia’s China-backed canal project will pose a security threat to Vietnam are wildly overblown.

Earlier this month, I wrote a column for Radio Free Asia (“The Funan Techo Canal won’t end Cambodia’s dependency on Vietnam”) arguing for some level-headedness in discussions of the potential construction of the Funan Techo Canal, which will cut through eastern Cambodia, connecting the capital to the southern coast. But a few more remarks are needed because of some rather oddball opinions espoused of late, including some made recently by Sam Rainsy, Cambodia’s exiled opposition leader.

He has claimed – for instance, in emails to several newspapers in which I was bcc’ed for some reason, so I presume it wasn’t private discourse – that the canal has “very limited economic interest” for Cambodia. The environmental risk assessments on the canal have not been made public yet, so we can hold off on the economic assessments. Phnom Penh reckons it could cut costs by a third, although that is probably an exaggeration.

Nonetheless, the canal holds a strategic economic interest in that, as I’ve argued, it ends much of Cambodia’s dependence on Vietnam’s ports. The canal would connect the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port to a planned deepwater port in Kep province and an already-built deep seaport in Sihanoukville. Currently, much of Cambodia’s trade, especially from and to Phnom Penh, goes through Vietnam’s southern ports, mainly Cai Mep. The Cambodia government reckons the canal will cut shipping through Vietnamese ports by 70 percent.

First off, at present, Cambodia’s ports don’t get that much trade, so they remain less developed than they could be. Neither does the Cambodian taxman get his money. So there’s an economic interest for Cambodia in having more of its trade go through its own ports. Moreover, it would end the risk of Vietnam essentially blockading much of Cambodia’s trade, should events prompt that, by not allowing it access to its ports. It did this briefly in the early 1990s. And Phnom Penh – if it’s thinking strategically, knowing it cannot guarantee that peace in the Mekong region will last forever – has an interest in ensuring that much of its trade is not dependent on another country. It is striking that the likes of Sam Rainsy, who has campaigned for most of his life to end perceived or real Vietnamese influence over Cambodia, can overlook this factor. Then again, it goes against the argument of some people who still think the Hun family is a lackey of the “yuon,” as the Vietnamese are often termed.

One also has to put this into perspective. Port construction is at a frenzy in the region. Malaysia is now trying to double the capacity of its largest port, Klang, which is also the second-largest in the region. Westports Holdings, the operator, will invest $8.34 billion over the coming decades to increase its annual capacity from 14 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) to 27 million TEU. Malaysia’s Sapangar Bay Container Port, in Sabah, will also be expanded. Thailand is pushing for a vast port development under its Southern Corridor scheme. And the idea of the Kra canal – either as a canal or a series of railways connecting the Gulf of Thailand with the Andaman Sea across the Kra Isthmus – is back on the table in Bangkok. So Cambodia isn’t alone in wanting to develop a canal or boost its ports’ capacity. Competition is hotting up among Southeast Asia’s ports.

None of this would have made international headlines if it wasn’t for the strategically sensitive issue of China’s role in the Funan Techo Canal; the suggestion being that the canal has military implications. China having special access to Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base is one thing. After all, it is a military base and is less than 30 kilometers from the Vietnamese coastline. If a maritime conflict were to begin between Vietnam and China over the South China Sea, having naval vessels stationed off southern Cambodia would essentially mean that China encircles Vietnam – it could attack from the north, east, and south.

However, I fail to see the military purpose of the Chinese navy being able to traverse up a relatively small canal into mainland Cambodia and take a sharp right and launch an attack on Vietnam via the Mekong. Presumably, the best option would be just to travel the 30 kilometers from Ream to the Vietnamese coast. And as I wrote in Radio Free Asia: “if you can imagine Cambodia allowing the Chinese military access to its inland waterways to invade Vietnam, why not imagine Phnom Penh allowing the Chinese military to zip along its (Chinese-built) expressways and railways to invade Vietnam? If you are of that mindset, then Cambodia’s road or rail networks are just as much of a threat, or perhaps more so, as Cambodia’s naval bases or canals.”

Sam Rainsy, for instance, has alternatively argued that the Funan Techo Canal “will provide Beijing with a continuous waterway, uninterrupted from southern China to the Gulf of Thailand, passing through Laos and Cambodia… The waterway will be suitable for transporting goods, including weapons and ammunition, from China to the Gulf of Thailand.” That makes some sense, but only if you consider it for less than a minute.

Yes, if a conflict were to start between China and Vietnam, Beijing might not be able to ship munitions or arms through the South China Sea to a fleet that would supposedly be anchored off the Ream Naval Base. But why transport it by river? First off, from the Chinese border with Laos to Phnom Penh, the Mekong River is about, what, 1,000 kilometers long? Maybe a little more, maybe a little less. So how long would it take a ship to travel that route? At least a week? Maybe longer? It’s certainly not quick. And if you’re going to do that, you’re going to have to get these ships through Laos’ entire stretch of the Mekong, which will raise diplomatic issues between Vientiane and Hanoi. Thailand might also have something to say about it, too. Plus, a convoy of large Chinese vessels sailing down the river is going to be rather conspicuous, so Hanoi would hardly be taken by surprise.

More to the point, what weapons and ammunition are we talking about? If the idea is that China could transport military equipment all the way along the Mekong to Phnom Penh, and thereafter via the Funan Techo Canal to its ships presumably moored off the Ream Naval Base, we have to be talking about naval munitions and arms. But those are not light. Quite frankly, you’re not going to be able to do it. The Mekong is too narrow for ships that could carry such equipment. So, too, is the canal. According to Financial Times, Vietnamese sources reckon “Hanoi retains leverage over Cambodia” because ships carrying more than 1,000 tons won’t be able to traverse the canal and so would still rely on Vietnamese ports for trade. Presumably, ships carrying naval hardware would be in the 1,000-ton range, so wouldn’t be able to pass through the canal either. Moreover, why would you want to put expensive naval equipment out in the open for several days, at risk from a swarm of Vietnamese drones that could easily disrupt the shipment?

If you’re not talking about large naval hardware, then what’s the point of moving arms down the canal? If you’re talking about China shipping guns, artillery, and other munitions for a land assault on Vietnam, the boats could simply carry along the Mekong all the way into Vietnam. Moreover, why wouldn’t China fly (smaller) weapons and munitions to a Cambodian airport, such as the suspiciously large one near the Ream Naval Base? That would take a few hours. And it would be cheaper. And it would be more secretive than putting all your weapons on a boat. And it would put Cambodia and Laos less at risk of diplomatic fallout. More to the point, if China wanted to ship military equipment to Cambodia, you could only really transport light, non-naval equipment, in which case you wouldn’t need a canal as you’re not heading to the sea with that equipment.

None of the insinuations make sense. Yes, it’s prudent to be paranoid about what’s happening at the Ream Naval Base. It is a military base! But concerns about the military implications of the Funan Techo Canal just appear paranoid.

Author : David Hutt

Cambodia to break ground on contentious Techo Funan canal in August

May 31, 2024 - CAMBODIA will begin construction of its Chinese-backed US$1.7 billion Techo Funan canal this August, Prime Minister Hun Manet said on Thursday (May 31), describing the development as a “historic project”.

The 180-km canal that will connect the Mekong River basin to the Cambodian coast has caused tension between Cambodia and neighbouring Vietnam, and sparked fears that it could be used by Chinese warships. Cambodia has dismissed those claims as baseless.

Acknowledging concerns about the project Hun Manet described the strategic infrastructure development as a “historic project” in the nation’s interest.

“A lot of people have asked about this canal and some said this and that, that it benefits Vietnam, China, or (is) an attack on Vietnam,” he said.

“Whatever they say, this canal on Cambodian territory is for the Cambodian people.”

Cambodia says the upgraded canal would reduce its reliance on Vietnamese ports, cut transportation costs, and benefit 1.6 million people living along the canal by providing better irrigation for farming.

The government is in talks with a Chinese investment company to help fund the project, Hun Manet said, but stressed the project would proceed regardless. “We must do it now, we don’t wait anymore,” he said. “We will begin construction in August.”

The canal upgrade, part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, will be developed by a major Chinese state-owned construction company, China Road and Bridge Corporation.

Cambodia has consulted China on the technical aspects of the canal, said Hun Manet, adding that the government had also negotiated for the majority of the workers to be Cambodian.

Slated to be completed by 2028, the project has the potential to reignite tensions between Cambodia and Vietnam.

Environmentalists and Vietnamese authorities have expressed concern about possible damage to the fragile Mekong Delta, a massive rice-producing region supporting millions of people downstream in Vietnam.

Cambodia denies this and has also dismissed speculation the canal could be used to allow access for Chinese warships.

Thursday’s announcement comes after close regional allies Cambodia and China held their annual 15-day “Golden Dragon” military exercises earlier this month. REUTERS

- In June, 2024

|

| Prime Minister Hun Manet addresses the launch ceremony of a multi-purpose port in Kampot province on June 6. PM via social media |

Funan Techo Canal groundbreaking set for August 5

June 6, 2024 - Prime Minister Hun Manet announced that the groundbreaking for the Funan Techo Canal is set for August 5, noting that 51 per cent of the investment in the project will come from Cambodian financiers.

“I would like to declare that August 5, 2024, is the date of the canal groundbreaking and we don’t need to wait until the first anniversary of the seventh mandate government.

“We have already selected the location for the groundbreaking ceremony. We have prepared the materials, equipment and the means.

"Anyone who tries to spread the notion that we cannot achieve this and attempts to turn people against the project should not bother. It will only exhaust you because we are ready to move forward and make it happen," he said during the launching ceremony of a multi-purpose port in Kampot province on June 6.

The prime minister’s announcement of the exact date comes a week after he initially mentioned in a ceremony in Kampong Speu province that the groundbreaking of the canal would occur in August.

“Previously, the investment company consisted of 100 per cent foreign investors. But now I would like to confirm that this project is no longer entirely foreign-owned. Cambodians will make up 51 per cent of the financing and will participate as the majority holders of the investment.

"In this established Cambodian investment company, we have our state-owned companies, including Sihanoukville Autonomous Port [PAS] and Phnom Penh Autonomous Port [PPAP].

“These two are co-investors with another private company, with these state-owned companies being the majority holders of the Cambodian investment,” Manet said.

The prime minister also rejected claims from some commentators that the state is borrowing foreign money to invest in the project.

He explained that the project is a private initiative where private investors borrow money from banks themselves to invest in building the canal and request the rights to operate it for 50 years.

Manet noted that during this period, the government and investment companies will negotiate to ensure mutual benefits. When the period ends, the investment company will transfer the project to the government for management. This is known as a build–operate–transfer (BOT) mechanism.

He explained that the government will not spend money on the project; instead, the investment company is responsible for the costs. He stated that the venture will provide opportunities for the benefit of all, particularly in the tourism and transportation sectors. He added that provinces, as well as those bordering the Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers, will be able to use the canal waterway for transportation.

“This investment involves our Cambodian financiers’ participating in the construction, and [the government] will neither spend the state budget nor borrow loans to invest. State-owned companies will invest like private entities,” he said.

The 180-kilometre canal will cost $1.7 billion and take four to six years to complete.

Yang Peou, secretary-general of the Royal Academy of Cambodia, supported the announcement of the date because it avoids further analysis and “vague” comments.

“This exact date announcement puts an end to the ambiguity expressed by some analysts and politicians and sets a specific timeline for the excavation of the canal. It also marks the establishment of a great historical structure in Cambodia. After the temples, this canal is a monumental project,” he told The Post on June 6.

“The canal will be beneficial to the Cambodian nation. When the government declares something specific, it means that this project will achieve certain goals. This is the hope of the Cambodian nation, which will be realised in the future through the specific announcement of the government,” he added.

Reporter : Ry Sochan

Cambodia Set to Break Ground on Contentious Techo Funan Canal

June 10, 2024 - Cambodia will begin construction of its Chinese-backed $1.7 billion Techo Funan canal this August, Prime Minister Hun Manet said, describing the development as a "historic project".

The 180-km (112-mile) canal that will connect the Mekong River basin to the Cambodian coast has caused tension between Cambodia and neighboring Vietnam, and sparked fears that it could be used by Chinese warships. Cambodia has dismissed those claims as baseless.

Acknowledging concerns about the project Hun Manet described the strategic infrastructure development as a "historic project" in the nation's interest.

"A lot of people have asked about this canal and some said this and that, that it benefits Vietnam, China, or (is) an attack on Vietnam," he said.

"Whatever they say, this canal on Cambodian territory is for the Cambodian people."

Cambodia says the upgraded canal would reduce its reliance on Vietnamese ports, cut transportation costs, and benefit 1.6 million people living along the canal by providing better irrigation for farming.

The government is in talks with a Chinese investment company to help fund the project, Hun Manet said, but stressed the project would proceed regardless.

"We must do it now, we don't wait anymore," he said. "We will begin construction in August."

The canal upgrade, part of China's Belt and Road Initiative, will be developed by a major Chinese state-owned construction company, China Road and Bridge Corporation.

Cambodia has consulted China on the technical aspects of the canal, said Hun Manet, adding that the government had also negotiated for the majority of the workers to be Cambodian.

Slated to be completed by 2028, the project has the potential to reignite tensions between Cambodia and Vietnam.

Environmentalists and Vietnamese authorities have expressed concern about possible damage to the fragile Mekong Delta, a massive rice-producing region supporting millions of people downstream in Vietnam.

Cambodia denies this and has also dismissed speculation the canal could be used to allow access for Chinese warships.

The announcement comes after close regional allies Cambodia and China held their annual 15-day "Golden Dragon" military exercises in May.

Why Cambodia Matters to the U.S.-China Rivalry

June 24, 2024 : Little could be more symbolic of the power struggle playing out in Southeast Asia than what is happening on the outskirts of Ream National Park, in southern Cambodia. China is building a naval base on the site of a former U.S.-built military facility, and appears to be settling in for the long haul. Vessels of the People’s Liberation Army have been docked in the area for months, and the two countries have conducted a series of substantial “Golden Dragon” joint military exercises from the nearby Sihanoukville Autonomous Port. China used the opportunity to showcase their army of “robodogs”-four-legged robots with rifles mounted on their backs-to the world’s media. These drills first began in 2016, shortly after Cambodia canceled joint exercises with the United States.

Relations between China and Cambodia have moved apace in recent years. Details of the Ream naval base built with Chinese aid were first reported in 2019. And, this year, in a further deepening of ties, Chinese-owned companies are due to start work on the Funan Techo canal, a 112-mile, $1.7 billion project that will connect the capital to the Gulf of Thailand. Upon completion, the canal could divert traffic from the Mekong River and establish a trade route for China, through Laos and Cambodia, that cuts out the need for passage through an increasingly pro-Western Vietnam. China and Cambodia have a “build-operate-transfer” financing agreement, which will see it remain in China’s hands for at least 50 years.

For China, this control serves a greater strategic purpose. In Cambodia, and in the regime of Hun Manet, it now has an “ironclad ally” beholden on its investment. Around 40% of Cambodia’s $10 billion foreign debt is owed to China. And this gives President Xi Jinping, and his ruling-CCP, enormous clout.

|

| A Chinese army man tests a machine gun equipped on a robot dog before participating in the "Golden Dragon" on May 16.Heng Sinith-AP |

The U.S. and Vietnam recently upgraded their relationship in an effort to counter this threat of Chinese creep in Southeast Asia. Just last month, a U.S. warship was driven away from the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea by the Chinese military, after it allegedly crossed into its territory. While another U.S. ally, the Philippines, is currently engaged in a fierce diplomatic battle over disputed territory in this region, which has resulted in the ramming and water-cannoning of Philippine ships. Although an international tribunal has rejected China’s expansive claims to areas of the South China Sea, it has persisted in occupying and building out several new islands, as well as maintaining a military presence across the region.

The role of Cambodia in China’s power-play within the Indo-Pacific cannot be understated. The autocratic Manet regime is a critical ally for China. The Chinese Foreign Minister was the first foreign official to congratulate, and then meet with, him following his inauguration as Prime Minister in 2023. And there is an increasing crossover in the tactics-and adoption of certain technologies, such as mass surveillance tools including CCTV, facial recognition software, and internet “firewall” technologies-that are being used to monitor and suppress regime critics, trade unionists, and activists. Independent news outlets have been shuttered, and female journalists, in particular, have become targets of harassment and many forced into exile.

Unfortunately, the U.S. response has so far been muted. On a visit to Cambodia this month, U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin said that his ambitions with Manet were to “sit down and talk about how [we] might have a more positive and optimistic path in the future.” The visit was “not about securing significant deliverables and achievements.” This suggests a fundamental misread of what is happening in Southeast Asia. While the Biden Administration seems to perceive Cambodia as an amenable partner, Manet is double-dealing Beijing and Washington.

|

| U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin listens as Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Manet speaks during a meeting at the Peace Palace in Phnom Penh on June 4, 2024.STR/AFP/Getty Images |

Evidence for this includes Cambodia’s repeated attempts to engage with U.S. officials to join the Washington-backed Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). At the same time, the Manet government continues to court investment from China, which remains its top direct investor.

For those in Washington, who are increasingly concerned by the rise of China and the looming threats to Western democracy not just in Southeast Asia but around the world, a reset is required with countries like Cambodia. The current all carrot, no stick approach risks further democratic decline in Cambodia and the growth of Chinese influence.

Last year, Democrat and Republican lawmakers sought to bring the Manet regime to greater heel, with the threat of targeted sanctions against key figures suppressing democratic institutions, political freedoms, and human rights in the country. Their draft congressional bill also called for a more defined set of U.S. policies toward Cambodia. While this congressional effort ultimately failed to get sufficient traction, it is the kind of approach that is essential to give teeth to U.S. ambitions to counter China’s influence in the region.

This is a critical moment, both for the U.S. and Southeast Asia. Treading lightly with repressive leaders such as Manet risks normalizing their continued assault on the freedoms and liberties of citizens of this region. It also begs the question of U.S. lawmakers, who are speaking out on the need to push back at Chinese creep in this region, but not doing enough to safeguard the values of democracy that they, and the citizens of Southeast Asia, so care for.

- In July, 2024

Concert and Firework for Funan Techo Canal Groundbreaking Celebrate

July 26, 2024

The Phnom Penh Capital Administration will hold a concert and fireworks display in Phnom Penh to celebrate the commencement of the Funan Techo Canal. The concert will be held on August 5, 2024 in front of the Koh Pich Theater in Sangkat Tonle Bassac, Khan Chamkar Mon, Phnom Penh from 4:00 pm to 7:00 pm with the first fireworks display with a second display at 21:09 on the Chaktomuk River in front of the Royal Palace.

This event will be held to celebrate the groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of Funan Techo Canal, which is a long-term initiative of Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen, President of the Senate and Chairman of the Supreme Committee, which will leave a great historical legacy for the people, the next generation and the whole of Cambodia for thousands of years to come.

In order to maintain security, safety, order and public order during the above celebration, Phnom Penh Capital Hall requested the people who have to travel around the concert venue to be understanding and tolerant, because this venue will be very busy due to the people invited to watch this concert in large numbers.

In particular, sand ferries of all kinds, boats and ferries carrying national and international tourists who cross the Chaktomuk River in front of the RIoyal Palace must navigate at a distance of at least 200 meters from the ferry during the fireworks.

As the same day :

Kep Governor plans concert and fireworks to celebrate Funan Techo Canal.

In order to mark the occasion of the groundbreaking ceremony for the Funan Techo Canal on August 5, the Kep Provincial Administration has prepared a number of events such as beach concerts, fireworks, parades, and beautification of the province with about 3,000 participants.

The administration also plans to remove beer billboard ads and replace them with messages of support for the canal project.

Kep Governor Som Piseth announced the plans at a meeting to summarise the work results for July and to discuss the upcoming work for August. .

Piseth said that Kep is one of the four provinces that the Funan Canal passes through, so therefore, on the opening day of the canal construction site on August 5 the provincial administration has prepared the celebratory events which will be attended by at least 3,000 government officials, military personnel, youths, students and the general public.

He explained that the provincial administration would continue to dismantle beer billboards on the main streets and replace them with congratulatory messages regarding the canal.

According to the provincial governor, the flag-raising ceremony on the main roads will start on August 1, while at temples and religious centres and people’s homes in the province they have also prepared loudspeakers to celebrate the opening day of construction on the Funan Techo canal.

It seems that Cambodia has already started building the canal :

Officials inspect Funan Techo canal site.

On the afternoon of Monday, July 1, Sun Chanthol, Deputy Prime Minister and First Vice-President of the Council for the Development of Cambodia, along with the Ministers of Public Works and Transport, Water Resources and Meteorology, Health, the Kandal Provincial Governor, and a team of experts from relevant ministries and institutions, conducted an inspection of the Funan Techo Canal Project site in Prek Takeo village, Samraong Thom commune, Kien Svay district, Kandal province.

The Funan Techo Canal Project represents a significant milestone in Cambodia’s inland waterway infrastructure, establishing a direct link from Cambodian rivers to the sea. This initiative promises numerous benefits, including reduced travel time, distance, and operational costs for ships both inbound and outbound.

It aims to expedite national economic development, and integrate water transport through expanded multimodal connections. Furthermore, the project is expected to mitigate road damage, alleviate traffic congestion and accidents, minimize flooding, and deliver a range of socio-economic advantages.

The groundbreaking of the Funan Techo Canal Project is scheduled for August 5, to be presided over by Prime Minister Hun Manet. The event will be celebrated nationwide with fireworks and drums, demonstrating widespread support for this endeavor.

- In Aug, 2024

Vietnam respects Cambodia's implementation of Funan Techno canal project

August 08, 2024

The Funan Techo Canal is planned to be 180km long, passing through provinces of Cambodia, with approximately 1.6 million people living on both sides of the river's section.

HÀ NỘI - Việt Nam supports Cambodia's development efforts and respects the country's implementation of the Funan Techo canal project, deputy spokesperson for the Vietnamese foreign ministry Đoàn Khắc Việt said in response to the launching of the project on August 5.

Việt said Việt Nam hopes to coordinate with Cambodia on the research and assessment of the canal project's comprehensive impacts so it can take appropriate measures to minimise the project's impacts on the Mekong River.

"The Mekong River is an invaluable asset for the people, and this is the intersection of the friendship and community of the people from three countries: Việt Nam, Cambodia, and Laos.

"Việt Nam hopes that all riparian countries including Cambodia will join hands to manage and develop the river, in a sustainable and effective manner, the water resources of the Mekong River for the benefit of the community and of the people in the region, as well as for the future generation, and the close-knit ties between the countries," deputy spokesperson Việt said at the regular press briefing in Hà Nội on August 8.

The Funan Techo Canal is planned to be 180km long, passing through provinces of Cambodia, with approximately 1.6 million people living on both sides of the river's section.

The project, slated to be finished in 2028, costs an estimated US$1.7 billion.

Cambodia's Ministry of Public Works and Transport said that the investment for the project is divided into two phases. The first stage, spanning 21km, is funded by local Cambodian companies, while the second (159 kilometres) is a joint venture between Cambodian enterprises (51 per cent) and the China Bridge and Road Corporation (CRBC) at 49 per cent, according to the Phnom Penh Post. - VNS

August 31, 2024

- In Sep, 2024

October 2, 2024

Ministry of Public Works and Transport rejects false RFA report that Funan Techo canal project has evicted 10,000 families.

An artist’s impression of a portion of the Funan Techo Canal. Ministry of Information

The Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) has stated that it would like to reject the false information, disseminated by RFA (radio Free Asia) related to the construction process of “Prek Chik Funan Techo” which has content is completely contrary to the truth and has been spreading false information on social media.

The Ministry of Public Works and Transport is pleased to inform the public that on September 30, 2024, Radio Free Asia in English published information on its website and Facebook account, stating that “Funan Techo project has demanded the evacuation of about 10,000 families and swallowed farmland along the canal, and has not yet paid clear compensation to the affected people.”

In connection with the release of this information, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport would like to reject the above information and find that RFA is using and disseminating false and baseless information for the purpose of misrepresentation, pollution and incitement related to the construction process of “Prek Chik Funan Techo” which is completely contrary to the truth and has been continuing to share that false information on social media.

The Ministry of Public Works and Transport would like to inform the public that the technical team of the Ministry of Public Works and Transport has completed a detailed study and conducted an in-depth assessment of the actual impact of the project on the people and the infrastructure system.

And the results of the scientific study show that the impact on the housing of a total of 2,305 households, covering an area of 180 hectares, and a total of 11,525 people will be affected.

Out of a total of 2,305 households, only 400 will be completely affected, while 1,905 other houses / families will be affected only in certain parts of the house, such as fences, roofs, walls, wells or pet shelters.

In addition, the impact could be on a total of 3,469 hectares of agricultural land, including 2,775 hectares of farmland and 555 hectares of farmland and 43 public properties, including 149,163 antennas, roads, light poles and trees.

At the same time, the technical team also conducted a detailed study and in-depth evaluation of the scientific impact on the environment and people’s lives, with the results showing that it does not cause serious impact on the environment and the people, as alleged by RFA.

October 2, 2024

Ministry rejects claims of removing 10,000 families to facilitate Funan Techo Canal project

No comments:

Post a Comment