The Viking and their ship

Of all the images that the word “Viking” conjures up, that of the Longship is one of the most memorable - and one of the few that the general public gets right. We know now that most Vikings didn’t have long, unkempt hair; that they would fight with other weapons than battleaxes; and that the horned helmet is not much more than a myth. But the image of the Longship endures, and rightly so. It is what defined the Vikings, and the Viking Age. Its impact, and its legacy, was as complex as the people themselves.

It was in their ships that fierce, hard-hearted raiders wrought devastation and chaos on the coasts of Northern Europe for centuries. It was in their ships that the Vikings opened up new trade routes from east to west, north to south, founding towns as far apart as Ireland and Ukraine. Kings and chieftains were buried with lavish ceremony in their ships to demonstrate the wealth and power of their dynasty. Those who would not live under such rule fled in their ships to found new colonies in Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Normandy. Armies would embark on their ships for wars of conquest. Explorers would return with stories of the ancient civilisations of the East, or strange new lands to the west. To this day, scholars argue as to what the word “Viking” means. Yet there would have been no Viking Age without Viking ships.

Not all ships of the Viking Age were the same, of course. Some were little more than dinghies, allowing people and livestock to sail from one island to the next. Others were built to follow the wind, unsure of where the next landfall would be. At the new ports being built on the back of trade and plunder, big beamed cargo ships would offload their wares, whilst long, sleek, dragon-prowed warships would turn at anchor, reminding all of the authority of the emerging kingdoms. Royal yachts could be buried with their owner in pagan splendour. Clapped out fishing boats might end their days as scrap, revetments for a harbour wall or sunk to block a passage to a fjord. Yet they, like their owners, shared a common heritage.

Regia Anglorum possesses the largest fleet of replica Viking ships on this side of the North Sea. Owning them, repairing them and sailing them gives us an insight into what life must have been like for the Viking sailors. For more about the Regia fleet of replicas and the experiences sailing them, please visit the Fleet section of this website.

Types of Ship

All Viking ships have several things in common; they are all clinker built, and all reasonably symmetrical front to back. This is true for the 6m long four-oared rowing boat found with the 9th century Gokstadt burial and the 36m long 33-oared warship dated to the middle of the 11th century. However, within these parameters there was a considerable variation.

The longships grab all of the glory. The most famous one is perhaps the most atypical. The grave of a great chieftain was excavated with great care in the 19th century, revealing a beautiful ship - now called the Gokstad Ship. This boat was 23m long and 4.8m broad. This is now thought to be a “general purpose” type; a ship excavated at Ladby in Denmark in the 1930s may be a more typical warship - it was about the same length, but only 2.9m wide. Being narrower, it was faster, but could carry less cargo - but then, this was a pure warship.

As the Viking Age progressed, the Warships got longer - and smaller! The larger ships would have been owned by the nobility - Kings or Earls - and they were statements of wealth and power. By the eleventh century the largest ships were often over a hundred feet long, with crews of up to one hundred men - all of them trained warriors, parts of the ship-owner’s retinue. However, there were smaller levy ships - one that has been found is less than 18m long. This was probably a levy ship - a vessel maintained by a group of villages for the purpose of defending their own coast. The Vikings were now attacking themselves.

The trading vessels were perhaps the hidden revolution in the Viking Age. They took the basic plan of the Viking ship, and instead of just stretching it forward, they stretched it sideways as well. They carried a large sail, and a small crew - maybe only six to ten people - and only had a few oarports at the front and back. No-one rowed in the middle of the boat – that was where the cargo went. One of the largest Viking cargo ships was found in Hedeby harbour - the great trading post of Viking Denmark. It was 22m long but 6.2m broad, and could probably carry around 60 tons of cargo - and yet at full load it only needed 1.5m of water to float in.

Most Viking trading boats were able to come ashore without the need of complicated harbour facilities, and yet carry many tons of cargo. This encouraged international trade and economic growth. Eventually towns sprang up to service this trade - the first towns in Scandinavia were based around such trading centres, all of Ireland’s first cities were Hiberno-Norse trading outposts, and the re-building of London in the 10th century (away from the Aldwych, the “old trading post”) was based around the reconstruction of the Roman wharves. Eventually, the trade became so lucrative that it became worthwhile investing in larger, more cumbersome boats and complex port facilities. This meant that the Viking trading ship began to lose out to the heavier, slower Cog in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Viking Ship Construction

All Viking ships are clinker built; the planks were overlapped at one edge and riveted together. In clinker shipbuilding you start build the outside first, and then put a frame inside it. The other style of wooden shipbuilding, used by the Mary Rose and the Victory, is called carvel. In this style, the frame of the ship is made first, and planks are attached to it. Carvel boatbuilding had been used in Roman times, and was still in use in the Mediterranean in Regia’s period. At the end of the middle ages, Carvel had overtaken clinker as the method of choice for making larger boats. Does this mean that clinker was a poorer method of making boats? Not exactly…

The advantage that carvel has over clinker is that it can be made using any quality of wood, whereas to make a Clinker boat, only the best wood can be used. Carvel boats are built with a strong frame, and the planks are almost there “just” to keep the water out. Because the planks on a clinker-built boat overlap, they add strength to the boat, so the frame can be lighter. It doesn’t have to hold the boat together, just transmit forces between the hull and the “propulsion” - the oars and the sail. The Vikings built their boats using simple tools – it has been said that you can make a Viking boat with nothing but an axe – but they used them in sophisticated ways. They followed the grain of the wood, to get the most strength and flexibility for the lowest weight. Carvel boats tended to be made with sawn timber. Saws are harder to make than axes, and they tend to cut across the grain. This means that they can cut any timber any way you like, but the result will be weaker and less flexible than an axe-cut timber. In general, the Vikings praised their boats for their lightness and flexibility - “Sea Serpent” is a good Viking ship name, and a good Viking ship will ride across the tops of the waves. A heavier carvel boat will tend to fall into them, giving a rougher (and slower) ride.

And the reasons that the clinker tradition stopped being used for larger vessels? Well, no-one is quite sure. However, we know from the Mediaeval ship found in Newport that there wasn’t enough good quality timber to go around. Ships were being built with multiple decks, which needed a heavy frame anyway to carry the cargo – or the new-fangled cannon that warships were starting to mount. The world was changing, and the heavy framed carvel boat was the one that survived that change.

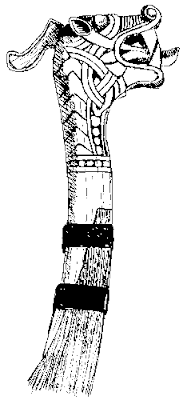

|

| A ships dragon head, from the version carved for Hedeby Museum. |

Master Shipbuilder

A master ship-builder would set the design for the Viking ship, and he started with the keel. However, it was the two curving posts at the front and the back of the ship - the stem and the stern - which would determine what sort of shape the finished vessel would be. It is from this vital first stage that he got his name - the Stem-smith.

The Stem-smith was probably responsible for making sure that the hull was the correct shape. This would involve cutting planks in ways that seem counter-intuitive to us; seeing the planks out flat can lead you to wonder how they ever could fit together. However, the stem-smith appears to have been an expert in taking a two-dimensional plank and turning it into a three-dimensional ship. It is only with modern computer modelling and an understanding of how boats move through the water that we are starting to see how sophisticated these shapes could be. For instance, Viking ships did not have deep keels, because there were few (if any) harbours that could take them. This meant that, when sailing with the wind anywhere other than right behind them, there was a tendency to be blown off course (mariners call this leeway). By changing the hull section of the boat, what has been called a “negative keel” can be formed - effectively using the boats speed through the water to increase the effect of the keel.

I am not, of course, claiming that Viking boat builders were imbued with supernatural powers, or knew modern hydrodynamic theory. It was simply the culmination of centuries of experimental boatbuilding, with the boats (and possibly boat builders) that survived being copied by the next generation. “Rules of thumb” would have grown up over the years. Plans as we know them would not have been used, although it is possible that a “boat ell” and marked plates and lines could have held useful information. On one of the vessels found being used to block a channel at Skuldelev, in Denmark, it was found that there was a relationship between the length of the keel, the size of the stem post, the number of planks, and the radius of curvature of the plank lines at the stem. Probably many boats, if not most, were built with a set of ideal proportions in the mind of the boat builder.

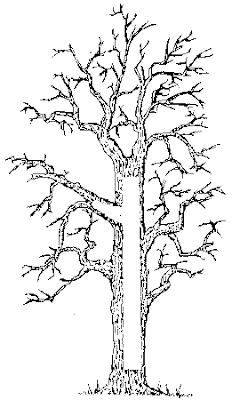

Wood for Shipbuilding

Timber was used green - in other words, shortly after felling. This is different to more modern practice, where the timber is "seasoned" - left to dry for several years. Green wood is easier to work, and more flexible, which can help with some of the more complex shapes found in Viking boats. Wood can be kept "green" for several years by keeping it immersed in water - a stem (or stern) of a Viking style boat was found on the island of Eig in what, a thousand years ago, had been a lake. As it had never been used - there were no indications of rivet holes – it was probably made up when the boat-builder had got a spare piece of suitable timber, and he was waiting for a similar bit for the stern (or stem) which never arrived.

It is also possible to steam green wood without complex equipment like the steam boxes used today. Simply by heating a plank over a fire, the moisture inside the wood heats up and causes the fibres to loosen. This means that - for a few minutes - it can be twisted into shape with less danger of it splitting and breaking. It is highly likely that this was done during Viking times - we know the technique was used to make "expanded" log boats, for example.

Oak or pine were the preferred woods to construct boats from. The only reason for using one over the other appears to be what was growing locally. There is, amongst marine archaeologists, a tentative division of Viking shipbuilding areas into “pine areas” (probably Northern Norway and Sweden) and “oak areas” (Southern Norway, Southern Sweden and Denmark).

Even in the "pine building" regions (mostly Northern Norway) Oak was still the wood of choice for the keel, so it must have been imported from the South. It's likely that masts and yards were made out of pine, so it may have been a two-way trade. The big difference between oak and pine is how planks are made from them. For oak, large straight trees of around two centuries old are cut, and then using wedges split multiple times like slices of a pie - it might be possible to get upwards of 60 planks from one tree. A pine tree will yield only two.

One advantage of pine over oak is that, as they age, pine planks will bend depending on whether the bark side of the plank faces the water or the inside of the boat, so they can be used to enhance the curve of the vessel over time.

The one boat definitely made outside Scandinavia, the “big longship” from Skuldelev in Denmark (Skuldelev 2), is made from Irish Oak. Most of the British Isles was probably an oak building area, although boat builders probably used the nearest timber to hand. Certainly some boats appear to have been repaired with anything, including bits of other boats!

Almost all planks found on Viking boats are made from what is known as “radially split” wood. This type of wood is virtually unknown today - you won’t find it at any timber merchants. It is, however, the strongest way that you can process wood, because it works with the grain of the wood - it gains strength by following the way that the tree grows. The log is split using an axe to make a cut, running up and down the trunk. The split is widened and extended by driving wedges into it, until eventually the whole trunk splits in half.

At this point, for a pine tree, the splitting stops. Younger pine trees are used, which are only about half the diameter of the an oak. Only two planks can be made from a pine tree with any success, and the two halves of the log are now shaved down along their length to remove the curved sections - a very wasteful process - so that they look less like two D’s facing each other and more like two planks. Oak trees can be split further; each half is split into quarters, each quarter split into eighths, and so on. In fact, from a 200-year-old tree, with skill, about 64 planks can be obtained. They are all slightly triangular, and quite rough, so they are smoothed down a little, like the pine planks.

For the frames inside the ships, the Viking shipwrights used another type of timber that is rarely seen today - the grown timber. A grown timber is simply one that has grown to the right shape. The grain runs in the direction that was needed, making the timber incredibly strong.

Viking ship frames are like display cases of grown timbers. For instance, the stem and stern posts would be taken from large, curved branches. Where two parts of the frame are to meet (usually a weak spot that needs re-enforcement) the Vikings used a single timber, cut from a branching element of a tree. On smaller vessels, where the oars didn’t pass through oarholes, the tholes (or rowlocks) were made from the junction of a branch with the trunk - putting the strongest part of the wood at the point of most strain.

|

| Logs are split rather than cut, as the split always follows the grain and doesn't cut across it |

Shipbuilding Tools

Shipping Tools

|

| A Sideaxe in use. The strake is wedged upright so that the axe can be used in the vertical plane |

The tools used for this smoothing would appear to us (at first glance) quite simple. An axe with a long blade could be used to smooth, as could an adze and a draw knife. Planes were known, and are shown being used for boat building on the Bayeux tapestry. Later on in the process, augers would start holes for rivets and trenails. Profiled irons would make decorative marks in the planks, or carve channels for caulking.

|

| One of the shipwrights team uses an adze to shape a embryo Sternpost. |

These apparently simple tools were so good that they remained unchanged for centuries - in fact, until the introduction of modern power tools!

|

| The Sideaxe is used to make split planks flat. It has an offset blade and a 'bent' handle to keep the users hands clear of the work |

Laying the Keel

To make a Viking ship, you lay down a keel first. The keel is made of Oak, as long and as straight as you can get. It’s not a flat piece of wood, but will have a T or a V shape to it, so that the first planks of the hull can be joined to it. Often this shape will change along the length of the keel, changing from a V section at the stem and stern (front and back) to a U section in the middle. This is to help shape the final lines of the hull.

Two pieces of curved wood are attached at the front and back of the keel, the Stem and Stern pieces. They are made from what is called “grown timbers” - wood that has been especially selected because it approximates the shape that is needed. There is some evidence to show that there was a relationship between the length of keel and the diameter of curve in the stem and stern pieces. Viking ships are pretty much symmetrical both fore and aft (front and back) and port and starboard (left and right), so the curve in these pieces will be the same.

|

| Trenails used to anchor ribs and strakes together |

Two types of stem and stern piece construction have been found. In one, the stems are simple curves. In the other, they are carved and notched with steps, forming the beginnings of the planks that they will eventually hold. Although this is a lot of work to do, it can save time in the long run. It was important for Viking ships to have the planks sweeping up and running together along the stems. The Gokstad ship, which has the “simple” stem and stern, has to use much more complex shapes on the planks to achieve the same effect as the later “Skuldelev” ships.

The keel is joined to the stem and stern posts by trenails – wooden pegs, “tree nails” if you prefer. It is then ready to have the planks (or strakes) put on it.

|

| An example of strakes lashed with bast fibre ropes to the ribs |

Building the Hull

The first strake to go on is called the Garboard strake (dunno why, it just is) and it is riveted and nailed on to the keel. Iron rivets are the most common Viking method of joining planks together (modern clinker boats use copper). Nails are used where the end of the rivet cannot be reached - usually at the stem and stern, where space is tight. The heads of the rivets are bent over rectangular (ish) washers, which are called roves. The next plank is riveted on to the garboard strake, so that it overlaps it when seen from outside. The rivet passes through the outside of the plank near its bottom edge, through the garboard strake near its top edge, and it is bent over a washer inside the boat.

|

| A Scarf joint roved through from either side. |

Caulking (or luting) is used to stop water from getting into the boats. No wooden boat can claim to be entirely watertight, but the Vikings did their best. The caulking was made from animal hair (such as sheep’s wool) that had been dipped in a sticky pitch made from pine resin. It was laid in the groove on the plank and, when the plank was riveted to the rest of the boat, created an almost watertight seal, whilst still having the flexibility to move with the boat.

|

| An example of roving. You can also make out the complex cross-section of the strake. |

As each plank is riveted to the next, the boat would begin to take shape. To get the boat to the correct profile involves cutting the planks into some fairly strange shapes. The way that the ends of the planks join onto the stem and stern helps determine the profile of the boat – whether it will be a beamy cargo ship or a knife-thin warship. The larger the ship, the more planks will be required. Long ships would require that several shorter planks be joined together by scarf joints – some of which could be quite elaborate. As the planks are added one above the other, clamps were used to hold them in place and the frame inside could be added.

|

| Another strake is wedged in place ready to be permanently roved onto the emerging ship. |

Framing the Ship

Once the shell is finished, it was time to put the frame into the boat. This is where this method of construction really scores. The frame has the job of transmitting forces from the “propulsion system” (the sail or the oars) to the hull, allowing it to move through the water.

|

| A finished Cabe overlaid on the other half of timber that it was carved from |

The hull is strong in itself - it doesn’t need a heavy frame to keep it together. Boats that are built “frame first” need a heavy frame as it has to deal with all of the forces on the boat - the hull is little more than a waterproof skin.

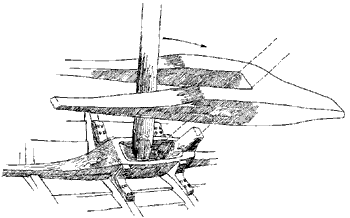

|

| One style ships used very heavy timbers as here with the Keelson and Mast Fish to anchor the mast in place |

There are a bewildering number of frame types for Viking ships, dependant (perhaps) on area of construction, time of construction, what the boat was used for, and (probably) what the builder was used to. Most frame systems have ribs that run across the hull, which join to timbers that run across to support a deck.

|

| Another style, the reliance on huge timbers to support the mast was replaced by rigging and lateral struts |

One important part of the frame was a long timber called the keelson. This sat inside the boat on the ribs, just above the keel. It had a hole or slot cut in it to take the mast, and on some of them a branch was left just in front of this hole to act as an extra support. This is another example of a grown timber.

|

| An example of some of the rigging using 'Virgins' to help anchor the mast |

Using a Viking Ship

On Board Ship

Hollywood is in love with the idea of rowing Viking ships. You can see why - it’s such a good visual look. Of course, all Viking ships were equipped with oars - there was no other way of propelling them if there was no wind, or if they needed to manoeuvre in harbour. The big beamy cargo ships would perhaps have two or three pairs of oarholes near the stem, and the same near the stern - the whole centre of the boat would have been taken up with the cargo. The oars would have been used only at the very first and last stages of the journey - leaving port and arriving at the destination.

| |

| A 44-oared warship striking out of the fjord as the mast is raised |

|

| The 60 foot merchantman or Knarr returns from overseas |

For the most part, Viking ships did rely on the wind. A cargo ship would have as few a crew as possible - the fewer on board, the larger each crewman's share of profit would be. The crews could (perhaps) hope to rely on the protection of a powerful patron, such as a King or a Jarl, to deter would be pirates. Certainly strong kings were eager to flush out havens of piracy such as the Kattegat and Skaggerak straits that guard the Baltic, and the Western Isles at the north of the Irish Sea. For warriors, ship time was (for the most part) a time to relax and conserve their strength. It was at their destination that they would need to do hard work. Games boards have been found scratched onto decks and chests of ships, and one particularly fine one has been found with pegs on it, just like a set of travel chess – giving perhaps a glimpse of how time was passed on board.

|

| On a quiet day, the ship can heave too and take the opportunity to cook a hot meal on the ballast |

Of all the dangers that the Vikings faced, the biggest one has remained unchanged - the sea itself. All Viking boats were “open” - that is, there were no lower decks in which to shelter. Whilst this might make them uncomfortable in heavy weather, with a risk of hypothermia, there was an even greater danger - that of swamping. If the waves were high enough to come into the boat, it would fill very quickly with water, and with no airtight areas under the deck, even if the vessel did not capsize it would be almost impossible to save it from being broken up. One Scandinavian reconstruction of a Viking vessel has been lost this way - fortunately, thanks to modern search and rescue, with no loss of life. In Viking times, the dangers were even greater, and the chance of rescue almost non-existent. This is why we are very careful when we take our boats out!

|

| The Viking crew get a little panicky at the sight of an unknown Arab ship, which is in fact a trader just like theirs, with a crew who are just as panicky |

Sails and Rigging

It was the sail that allowed the Vikings to make their great journeys of trade, raid, conquest and exploration. Unlike the hulls, no sails have been found from ships of the Viking age. However, some fragments from a 14th century woollen sail were found in a church in Norway. Since churches were often used to store parts for Longships (at least after the conversion to Christianity!) this seems a likely place to find a sail.

Wool seems a strange choice to make a sail out of at first. It has a lower strength to weight ratio than linen or hemp, both of which were available as well. However, made the way that the Vikings used it there are several advantages. It has a natural stretch, which makes it more efficient when sailing into the wind. The ability to stretch means that it is less likely to burst in a squall. The stretchiness of the sail also means that it can act as a shock absorber, softening sudden strain off the rigging. It has been estimated that making the sails and ropes for a Viking ship would probably take just as long as making the hull.

For the textile geeks, the yarn was from a “primitive” breed of sheep, such as the Vilsau; The warp of the weave contained the majority of the long hair of the fleece and had a hard, Z-spun twist, whist the weft contained the shorter hair and was softly S-spun. The fabric was woven into a 2/1 twill with between 8 and 9 warps per cm, and 4 to 6 wefts per cm. It was probably not fulled, but it was “smorred” - that is, it had multiple applications of animal fat and ochre rubbed into it. The animal fat would have preserved the sail, waterproofed it, and improved its wind-holding performance. The ochre would have helped with this, and also may have coloured the sail. The result is a fabric which weighs about 1kg per square metre, and has a texture described as “leather-like”.

Ropes on a ship are usually called “rigging,” and are usually categorised as “standing” and “running.” Standing rigging is the sort that is used to stop the mast from falling over - it’s designed not to stay put, and isn’t handled much. Running rigging is used to control the sail, and will thus be going through people’s hands all of the time. This makes the texture of the ropes very important - cut and rope-burned hands are no good on a ship, and ropes that jam in holes or pulley blocks are nearly as painful! Horsehair would have been the best rope to use for running rigging, as it is soft to the touch. Linen and hemp could also have been used. For the standing rigging, “bast” - the fibre found under the bark of the oak or the lime trees - could be used instead. The Halyard (the rope used to pull the yard, and the sail that is attached to it, up the mast) has to be the strongest rope on the ship. The very best were made from the hide of a walrus - not something that modern ships can boast!

|

| An example of some of the rigging using 'Virgins' to help anchor the mast |

The Sailors

The sort of person that you would find sailing a Viking boat would depend on what sort of boat it was. The classic “raiding” boat would have consisted of a crew drawn from the middle ranks of society - the small landholders. One of the theories for the cause of the Viking age is an increase in the population of Scandinavia. With more people living in the same amount of land, there was less land to hand out; people would either have to face poverty and starvation, or search abroad for new opportunities.

Some of the Viking ships may have been communally owned. There is the tale of a French boat who tried to stop a Viking boat to speak to their leader. The response that came back was “that they were all equal!” At the end of the Viking age, Kings set up a levy system for home defence, where everyone in a town or village was responsible for the upkeep of a “local” ship; it’s thought that one of the Viking ships found blocking the entrance to Roskilde harbour was one of those. These ships would almost certainly never leave their home waters.

|

| The steersman doesn't have to work too hard at the tiller, which is a good thing in poor weather |

When the King or magnate wanted to go abroad, either for warfare or just to impress his neighbours, he would use his big Longships. These would be manned by his personal warriors, who would also be expected to know the rudiments of sailing. It was considered a noble achievement to be able to sail a boat. Depending on the size, a fully manned Longship could carry forty to one hundred people, so co-ordinating them would have been quite a feat of man-management.

No-one knows who owned the trading ships for sure. It may be that they were a communal effort from amongst several “well off” families in a geographical area, or that a local magnate would have had them built. The crews would have been much smaller than for a longship - perhaps eight to twelve people - as most of the space would have been needed for cargo. All would have been known to the owners, and perhaps they would have been expecting a share from the profits.

|

| The crew pull for all they're worth to get the warship off the jetty on a breezy day |

Controlling the Ship

- Viking anchors had a wooden crossbeam that slid up the shank of the anchor to a point where the anchor was round in section. It could be rotated to either lie flat for storage on deck, or crosswise to ensure that the flukes dug in on the sea bed

- A 'wooden' anchor some 3 feet across weighed down with the aid of a carved waisted large rock

- The usual layout of the Tiller and Rudder.

No comments:

Post a Comment